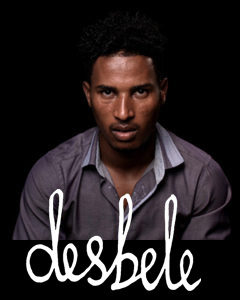

Desbele Haile Kahsay (1998), Eritrea

Desbele has a fairly normal life: he goes to school, and in his spare time he plays football with friends. But Eritrea is a dictatorship where people are not free. When Desbele is sixteen he decides to flee with a friend, leaving his parents, four brothers and sister behind.

The two friends first arrive in the neighboring country of Ethiopia. Then they travel with a group of forty people to Sudan, staying there for two months, in extremely poor conditions. They continue on to Libya, where Desbele is regularly assaulted, mainly because he is a Catholic. After a month they set off in an overcrowded and rickety boat for Italy. After passing through Rome, Milan and Munich, he reaches the Netherlands in 2015. His friend takes another route and ends up in Germany.

The North Korea of Africa

The dictatorship in Eritrea is not often in the news. Even so, Eritrea is one of the most unfree and dangerous places to live. The country is often referred to as ‘the North Korea of Africa’. Criticism of the government is not tolerated, and there are no opposition parties, independent media or social organizations. Opponents of the regime and their families run the risk of being arrested and tortured. Over 350,000 Eritreans have fled to other parts of the world.

Many Eritreans flee because of conscription, which normally lasts eighteen months, but in practice it is often extended for up to twenty years. Conscripts receive little payment, not enough to support their family. Conscientious objectors and deserters are harshly punished, and their family members also run the risk of being rounded up.

Fleeing the country is not without risk: a ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy is adopted for everybody who tries to cross the border illegally. Even if they succeed, Eritreans face a long and often traumatic journey to Europe. Accounts of the journey across the Sudanese desert are harrowing: shortages of water and food, and assaults by human smugglers. Many refugees do not survive this leg of the journey. They also suffer discrimination in Libya. And then comes the sea crossing to Europe in a rickety boat, even though many of the refugees cannot swim.

The boat people

Every year hundreds of thousands of refugees risk the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean Sea to Europe. Desbele is one of them. A boat person is someone who, for political or economic reasons, escapes his country by crossing the sea. The first modern boat people were Vietnamese refugees who, after the Vietnam War, fled their country in the late 1970s in tiny boats that were often not seaworthy.

Many refugees from Africa arrived in Spain in the late 1990s. In 2013 and 2014, Italy was the most important land of arrival. Since the spring and summer of 2015, that has been Greece. Routes change when new obstacles — such as tighter border controls — are put in place, but the destination remains the same: Europe.

Owing to the wars in Libya, Mali, Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria, the number of refugees arriving in Europe started rising sharply in the spring of 2014. Boats full of Africans, and later Syrians, attempted the crossing. Almost every day the Italian coastal guard brought people ashore onto the Italian island of Lampedusa. They had been rescued from vessels left drifting out at sea by human smugglers. The European Union also deployed additional airplanes and ships to rescue people at sea. But a real solution has not been found. For many people, help arrived too late.

In two years (2014-2015), one and a half million people risked the dangerous crossing to Europe. More than 10,000 of them died on the journey, more than anywhere else in the world. For those who do manage to reach land, the Greek or Italian islands are not the final destination, but simply a stopover on the long journey through Europe: to Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, or another country in northern Europe.